NGC 6826 - "Blinking Planetary Nebula"

The "Blinking Planetary", as the planetary nebula is also called, is located at a distance of 2,200 light years in the constellation of Swan and has the

number 6826 in the "New General Catalogue". Due to its brightness of 8.8mag it is a great object even for small telescopes on balmy summer nights.

The nebula itself has an apparent size of 27" (arcseconds), from which we can derive a true diameter of 0.29 lightyears. This is equivalent to 2.7 trillion

kilometers or 18,200 astronomical units. A rather large gas envelope if you think about it...

Besides the inner shell, there are two other features that make the PN a very exciting object. First, there is the bright inner ring. This ring is formed

because the hot central star blows a strong stellar wind into the old material. A hot bubble is formed. Where this bubble meets the already existing

material, the gas is compressed, heats up and starts to glow. The second feature is two small luminous blobs on the long axis of the planetary nebula.

These are also known as "FLIERS." Here, two faintly ionized gas clouds plow through the old nebular envelope at supersonic speeds along the axis

of symmetry. Quite striking! There is also a very faint outer halo with a diameter of about 140 arcseconds. So we see, the nebular envelope of the

"Blinking Planetary" has a lot to offer.

But the central star is not bad either. With a visual magnitude of 10.4 mag it is one of the brightest stars you can find in the center of a PN. It is so

bright that the nebular envelope seems to disappear when looking directly at the central star. If you alternate this direct/indirect viewing, the planetary

nebula appears to twinkle in small telescopes. Mystery solved. :) The apparent visual magnitude can be converted to an absolute magnitude of

M=1.3mag or to 27 solar luminosities using the known distance. However, the bolometric magnitude is even 1,600 times that of the Sun, although

much higher values can be found in the literature. The central star is very hot with a surface temperature of 50,000 Kelvin and thus belongs to the

spectral type O3. With the help of photometric measurements a light change with a period of a few hours was also detected. However, these are not

visually visible because of the very low amplitude of 0.03mag.

After so much exhausting theory we finally come to the sight in the telescope:

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

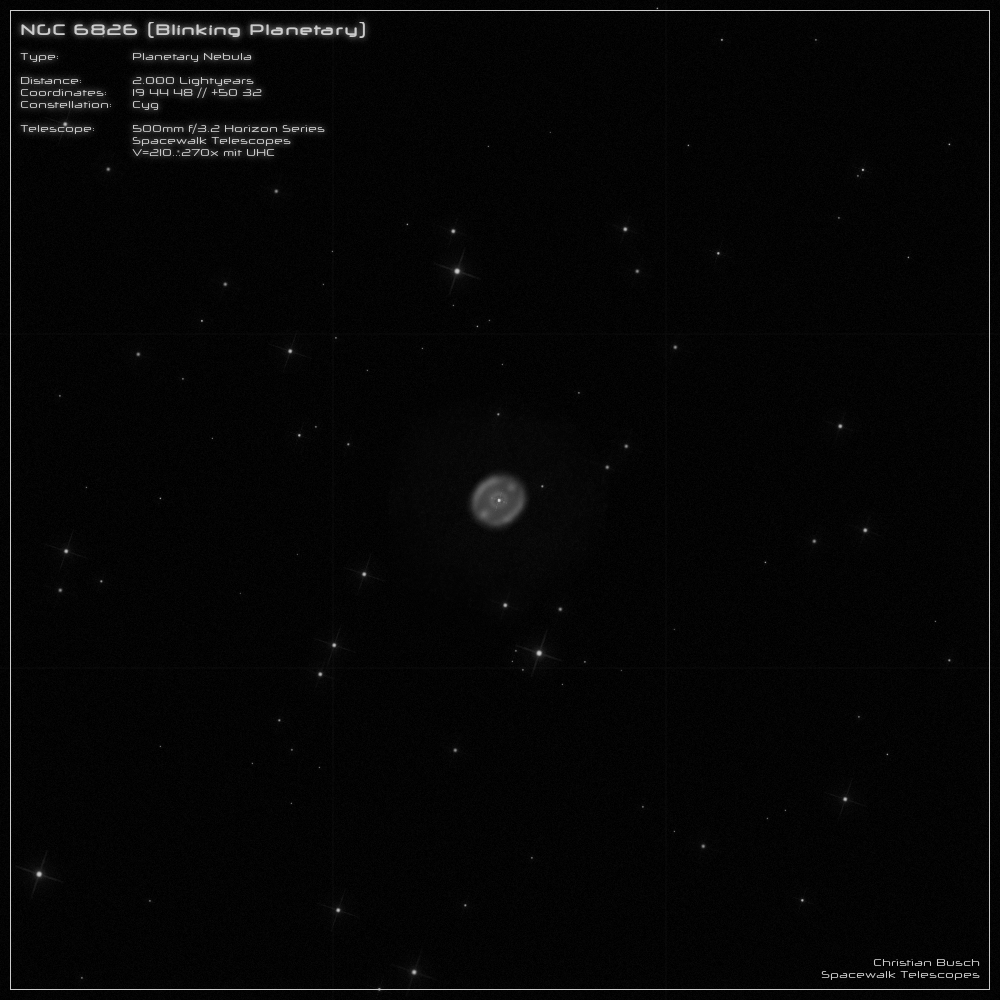

The nebula is found quickly and appears quite bright in my 20 inch at 120x. Also the central star can be seen without any problems. However, with

such a large aperture, you can skip the blinking. The nebula is simply too bright for that and can be seen even if you stare directly at the central star.

But it gets really exciting when you increase the magnification to 380x. Because I like the greenish-turquoise glow of NGC 6826 so much, I prefer

to observe it without a filter. First of all, the long sides of the PN appear slightly brightened compared to the rest of the surface. The inner ring is also

faintly visible. Here the bright central star disturbs a bit. Also the two FLIERS are not so easy and need a dark sky. But with a little patience all details

can be worked out well. It is really exciting.

And the outer halo? First of all, you have to know that it exists. Otherwise you'll quickly miss it. And without a filter nothing works here either.

With a UHC at 120x I could see the halo faintly but surely with indirect vision. I was even of the opinion to have seen the edges of the halo slightly

brighter. But I was absolutely not sure, so I did not include this detail in the drawing. But at least I made a note of it.